This is an extract from Living Off the Land – A Manual of Bushcraft, 1944, updated 1967 by H.A. (Bill) Lindsay, one of ABW’s founders. While some of the methods detailed here are far too destructive for everyday use, they may serve well in an emergency.

When the average civilised man, who knows nothing of the bush, finds himself stranded in scrub country, he is usually under a heavy handicap because he has what can be called ‘the water-tap outlook’. In his mind he associates a drink of water with the turning of a tap, or thinks of it as something which lies in pools or runs down creeks. He cannot visualise it as existing anywhere else. As a result he walks around looking for streams or pools, wasting his strength in useless labour; and only too often he fails to find what he seeks.

An Aboriginal or a good bushman, on the other hand, would know that you can find water in places other than creeks, wells, springs, and taps on pipe-lines. It can be drained from the roots or the trunks of many of our native trees and shrubs; it lies in the distended bodies of frogs which have buried themselves under the mud of dried-out swamps and lagoons; it can be found by digging a hole in the right place; it pours out of some of the canes and vines to be found in jungles; many species of bird will indicate that it is near or lead one to it.

As a result, good bushmen and Aborigines will find water where the untrained man can die, and often has died, of thirst.

Let us carry this illustration further. Imagine yourself stranded somewhere in the scrub country of the southern portion of Australia. Overhead the midsummer sun blazes from a cloudless sky; underfoot lies a soil of reddish sand in which it is hopeless to try to find water in the shape of soaks, creeks, or pools. All around, stretching to the rim of the horizon, is a leafy wilderness of low trees. You have no water and your throat is parched. What should you do, and, equally important, what shouldn’t you do?

The worst thing would be to start walking as fast as you could in any direction, driven by a sick panic and hoping to find a track or a fence which might lead you to a house, a hut with a rainwater tank, a well, or a bore. If an Aboriginal was watching he would probably sum up the position by saying:

‘White feller big feller fool!’ He would be right.

Collecting Water From Roots

Contrast the above with what a good bushman would do if he was in the same position. He would look around, to see a ridge slightly higher than the surrounding country. He would move towards it with unhurried, energy-conserving steps, his mind calm and his intention being to let his eyes save his legs from a lot of useless work. On reaching the crest of the ridge he would tilt the brim of his hat over his eyes to shield them from the glare and survey the scrub looking for water trees.

His gaze would become fixed on one spot, where he had picked out a large, luxuriant clump of water-yielding mallee, a needlebush bigger than usual, a banksia, or any other tree or shrub whose roots will yield water. He would walk towards it, husbanding his strength by not hurrying and also conserving his body moisture by not raising a profuse perspiration. As he strolled along he would break a stout green stick and trim one end to a point with his knife.

What if he had no knife? In that case he would not be a good bushman so there is no need to consider the possibility.

If the ground was very hard he would have to light a small fire, char one end of the stick, scrape it with his knife, char it, scrape again, and so on until it had a hard point. But in this sandy soil he would not need a fire-hardened digging stick.

Upon reaching the tree or bush which he had selected he would not dig up the ground in all directions, hoping to find a water-root by hit or miss methods. If the tree or bush is small, a heavy push against the trunk causes the ground to crack above a root. In the case of a bigger tree, the position of the roots may be indicated by slight ridges in sandy soil. These show up most plainly at sunrise or sunset, when the shadows are long. If the soil carries grass the course of each root is marked by lines radiating from the trunk on which little or nothing grows.

Our bushman digs in one of these spots about a metre out from the trunk. At any depth from a few centimetres to half a metre he strikes the type of root which yields water. It is never very thick; it ranges from the size of a thumb to that of a man’s wrist. The bark is smoother than that of other roots, it does not send out a lot of side branches, and it is even in thickness, with little or no taper. It does not dip sharply under the ground but runs more or less parallel to the surface.

A slanting cut is made through the root, the free end is grasped in the left hand, and the right hand pushes the digging stick under it and uses it as a lever. The soil lifts and cracks as he works and the root comes up as if it was a rope which had been buried. He may get 5 to 10 metres of it before he comes to the spot where the main root branches into many small ones.

Now he uses his knowledge of elementary botany. He knows that the fine, almost hair-like rootlets at the tips of these roots run in all directions through the soil and that moisture enters them by osmotic pressure. This water travels along the root to the trunk, then up the trunk to the leaves.

He also knows that it is necessary to use slanting cuts to get a quick flow. He divides the root into half-metre lengths, the end of each piece which was nearest to the trunk is placed downward, and the water drains out, because this is the natural direction of the flow.

When the water ceases to drip from each piece of root, our bushman secures a little additional water by putting his mouth over the top end and blowing down it, catching the drops in his cupped hand or the crown of his felt hat. The hundreds of times during the last war, the writer staged the foregoing scene to classes of Army and Air Force personnel. In every case, sufficient water to keep a man going for 24 hours was obtained in the manner described. It was not unusual for one 6-metre length of root, no thicker than a broom handle when the bark had been removed, to yield about 600 milli-litres of clear and almost tasteless water; and 9-metre roots often yielded nearly a litre.

Here are the rules for collecting water from roots in scrub country:

- Always select the greenest and most luxuriant-looking tree or bush in sight.

- Always put the end of each piece of root which was nearest to the tree downward when draining out the water.

- Avoid dense scrub; select trees or bushes which stand alone, or on the outside of a clump.

- Don’t search for water on rocky ground. Choose soft soil or sand. On rocky ground it is hard to dig out the roots and if you do get some they are gnarled and distorted. Water does not run readily from them.

- Disregard the advice which used to be given — one suspects by people without practical experience —’Go into the hollows’ when seeking water-roots. The best places are on rises, particularly sandhills, where a tree or a bush has to develop an extensive root system in order to live.

- The best time to get the water is at sunrise, when the tree has been collecting and storing water during the night and the roots are turgid (full). The worst time is in the middle of a hot, dry day.

- The water from the roots of some species of tree has a gummy, earthy taste, but from others it is almost as good as rainwater. There is no need to sterilise it. Nature has done that.

- There are only two ‘don’t drink it’ rules. Don’t use the water from the roots of shrubs or bushes if it has a bitter taste or burns the tongue; shun anything which runs from a root whose bark exudes a milky juice.

- All water-roots are of the same colour right through and the pores in them are visible to the naked eye. No water will come from the bigger roots having a thin layer of sapwood surrounding a hard, dark core of heartwood.

Main Water-trees of Southern Australia

Around Carnarvon, Western Australia, there is a scrub wattle, very similar to the jamwood in appearance but, where the wood of the jamwood has a chocolate colour and smells like raspberry jam when cut, the wood of this wattle is light in colour and much softer. The leaf, like that of the jam, is long and thin but slightly wider and without the very fine, fluffy hairs on the edge.

Although found inland as well as on the coast, it is usually known as coast wattle and is the main vegetation on the coastal dunes as far south as Fremantle. Its roots yield a lot of water for their size. Inland grows another acacia with thin, needle-like, but slightly flattened leaves, soft to the touch, with the tip of each bent a little to one side, after the style of those on the familiar Geraldton wax plant. It is another tree whose roots yield water.

Further south, and for some distance inland, several species of banksia are common. As is the case in nearly every other part of Australia where banksias grow on sandy soil, these are good water-yielders. The trees mentioned above extend inland in some places to where they are replaced by the salmon gums and gimlet mallee of the semi-desert.

In the latter type of country, generally known as the goldfields area, there is only one real water-tree; Grevillea nematophylla. In appearance it resembles a small she-oak, except that the leaves are smooth, like pine needles. The fruits resemble those of the silky oak, being dark brown in colour, oval in shape, about 16 millimetres in length, and they split down the side to release the seed. The water from the roots of this little tree has saved a number of lives.

The forest country of the south-west of Western Australia will be passed over for the time being, as a different method for obtaining water from trees is used where the timber grows close and tall. Along the coast east from Albany the country is again semi-arid and here the water-tree is the blue mallee, whose leaves are as large as the palm of the hand and of the same grey-blue colour (glaucous) as the juvenile foliage of the bluegum. Inland grows the Calothamnus bush; its flowers resemble those of the bottle-brush split lengthwise. The water is in sausage-shaped swellings on the roots.

To the north, out in country which is almost dry enough to be classed as desert, there is another tree with these curious water-filled swellings on the roots: Brachychiton gregorii, better known as the Desert kurrajong. In appearance it is so similar to the other species of kurrajongs used in Australia for street and park planting that no description is necessary, expect to say that it can be identified at a long distance by its foliage of large light green leaves.

Further east, around the fringes of the Nullarbor Plain, grows the most famous of all water-yielding trees, Eucalyptus oleosa. In some old botanical books it is listed as E. transcontinentalis. To the beginner most mallees look very much alike, but it is easy to identify this one. When the bark is shed it does not flake off, as is the case with most mallees, but comes away in long ribbon-like strips which may hang for months. When these strips fall off eventually they lie flat on the ground, radiating from the trunks like the spokes of a wheel.

During his explorations in this part of Australia an uncle of mine, the late David Lindsay, met family groups of Aborigines who, all through the dry summer months, had little water except what they managed to drain from the roots of this tree.

On the eastern side of the Nullarbor the water mallee is again found, running down into Eyre Peninsula on the south and well into Central Australia to the north.

South from the Murray mouth there is an extensive area of sand dunes on the seaward and landward sides of the long Coorong salt-water lagoon. Here there grows a wattle, Acacia sophorae, forming the only vegetation of any size in many places. The long roots are often exposed by wind erosion.

Water runs from them when they are cut and up-ended, yet in the early days of European settlement several men suffered severely from thirst in this area and a few died, never realising that there was plenty of water in the roots over which they tripped and stumbled.

Inland from the Coorong area and running out into the ‘Sunset’ country of the north-west of Victoria is a big area of low scrub in which there are several species of mallees whose roots yield water, as well as the Hakea (needlebrush), easily recognised by its stiff, round, dark green leaves, each with a tiny, hard black spine on the tip. The woody fruits are shaped something like a kidney.

Much of this country is cleared and settled. Only in a few areas would anyone now have to go far in order to encounter a house, a bore with a windmill and stock troughs, or a track which would lead to a road. But it forms a very good training area for anyone who wishes to learn bushcraft.

Other large areas of country in southern and central Australia have trees or shrubs whose roots will yield a drink of water in an emergency. It is a curious fact, however, that our botanical handbooks contain few or no references to this vitally important feature of some of our species of native flora, while one so-called ‘bushcraft’ handbook, published during the last war, contained downright misinformation.

It is most important for the student to visit, as part of the training, an area of semi-arid country and there try his or her hand at obtaining water from tree roots. It will be found to be much easier in theory than in practice. But gradually the knack of selecting the right specimens of any species will be acquired; it is also calculated to bring home the fact that by practice alone can one master all the things needed to become a real bushman.

But a warning must be given against thinking that one who has mastered this particular phase of the work can then get a drink in any other area of scrub in Australia, especially when drought has the country in its withering grip. Further, there are extensive tracts of country where no water-yielding flora of any kind is growing. The writer traversed the 160-kilometre belt of scrub between Exmouth Gulf and Carnarvon, Western Australia, without finding as much as a solitary specimen, and there are other areas like it.

Other Methods

There remains one trick which may save a life when all else fails. Anyone who is forced to cross a stretch of bad country on foot should copy the desert Aborigines by carrying a piece of good red or yellow clay about the size of a billiard ball.

Clay of this type can be obtained from creek banks, from the subsoil on the roots of a tree which has blown over, from the mound around the entrance to an ant’s nest, or, as a last resort, by digging in a suitable spot with a pointed stick.

It is advisable to procure the clay at the first opportunity and carry it in case it is needed; one should never rely on finding things like this when and where they are required. If roots are dug up to get a drink and no water runs from them, blow down one to force a few drops of water from the other end. Use them to moisten a pinch of the clay into a putty-like paste. On the end of a l-metre piece of root which is farthest from the tree make a smooth, slanting cut, smear the clay over it, and with the ball of the thumb press it into the pores of the wood to seal them.

Light a small fire and warm the root in it, starting near the clay sealing and working slowly towards the other end. The heat liberates moisture from the wood, and steam pressure inside the root, which cannot escape through the clay sealing, forces all this water out of the other end, just as it can be seen to bubble and drip from the ends of wet or green sticks placed in a fire.

This will also work with smooth, straight sticks cut from the upper limbs of many species of gumtrees, but in this case the clay sealing is always placed on what was the lower end of the stick when it was growing. Choose sticks which will be about the size of your wrist at the larger end after the bark has been knocked off; this must be done in order to apply the heat direct to the wood. Water which has been steamed from roots or branches has a very strong gummy, astringent flavour but it is better than none.

Another and even simpler method of obtaining water is to use a number of fairly large plastic bags—if available. They must be completely free of holes. Gather as big a bunch as possible of gumtree or mallee foliage together on the end of a growing limb, hold it with a few turns of string, slip a plastic bag over it, and tie its mouth tightly to the limb so that no water vapour can escape.

Before long, little beads of water, transpired by the enclosed leaves, will be seen forming on the inside of the plastic bag. These gradually coalesce and run to the bottom corner of the bag. Shaking each bag every half hour or so helps to collect the water in the corner. Most people are very surprised at the amount of clear water which can be obtained in this way in the space of a few hours with the aid of three or four fairly large plastic bags.

Finding Water In Eucalypt Forests

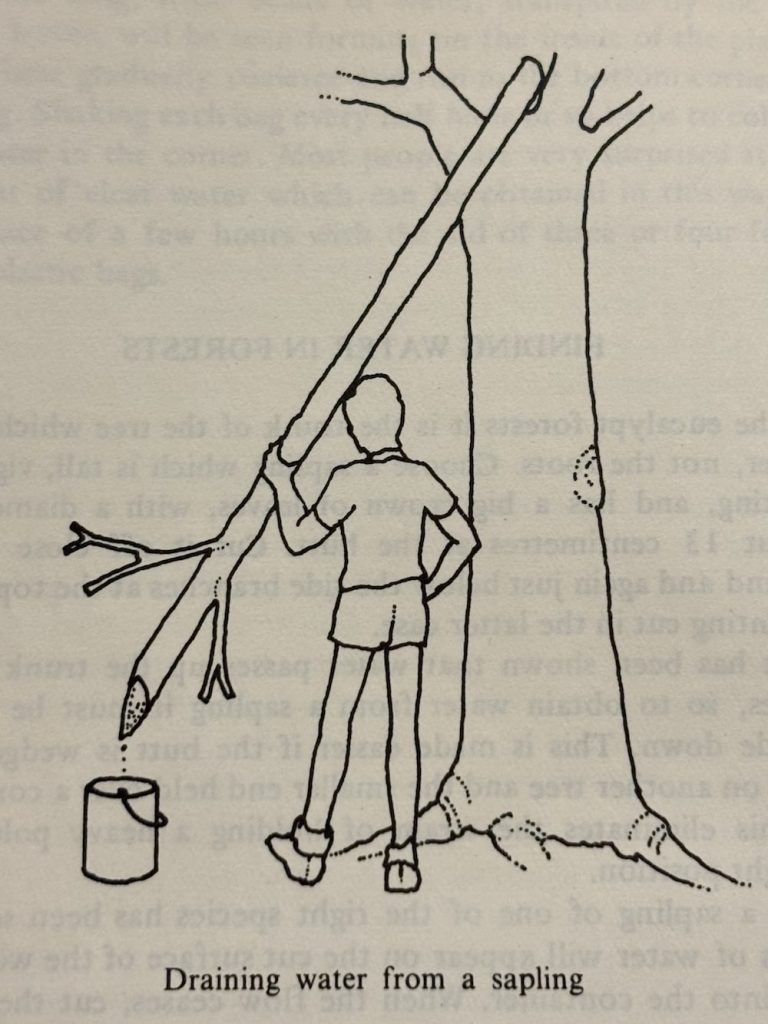

In the eucalypt forests it is the trunk of the tree which yields water, not the roots. Choose a sapling which is tall, vigorous-looking, and has a big crown of leaves, with a diameter of about 13 centimetres at the butt. Cut it off close to the ground and again just below the side branches at the top, using a slanting cut in the latter case.

It has been shown that water passes up the trunk to the leaves, so to obtain water from a sapling it must be turned upside down. This is made easier if the butt is wedged in a fork on another tree and the smaller end held over a container, as this eliminates the strain of holding a heavy pole in an upright position.

If a sapling of one of the right species has been selected, beads of water will appear on the cut surface of the wood and drip into the container. When the flow ceases, cut the sapling in halves, reject the thicker portion, and the flow will start again. When this ceases in turn, cut it in half again, knock the bark off the thicker end of what was the top section when the tree was standing, and blow down it to force out the last of the water.

A 3.5-metre sapling should yield up to 600 millilitres of clear and almost tasteless water. As is the case with roots, most water is obtained at sunrise; least in the middle of a hot day.

In the latter case, if one is badly in need of a drink and turning the sapling upside down, cutting it in halves, and blowing down it have yielded only a few drops, some very gummy-tasting water can be driven out by claysealing the last piece and heating in a fire.

No water will be obtained from the saplings of any species of tree if they show clearly defined annual growth rings when cut. It will come only from those which are of sapwood right through.

In the far north of Western Australia very few trees or shrubs will yield water from their roots, but nearly all the young saplings of eucalypts and tea-trees will yield water from their trunks, even out on the pindan plains which are barren during the dry season. In the latter case one must select either trees which grow on the banks of watercourses, even if these are creeks which run only after a heavy rain, or those growing on flats and having a heavy crown of foliage, giving them a healthy, flourishing appearance.

Further south, missing that stretch of bad country south from Broome and well-named ‘The Madman’s Track’, there is an extensive area where the creeks, which are dry for most of the year, are lined with trees. The young saplings growing among the bigger trees will run water, especially the species with a smooth bark which looks very like the river red-gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) of South Australia and Victoria, as well as another species whose equally smooth white bark is covered with a flour-like powder which rubs off on the hand.

Further south again the flooded gum, Eucalyptus rudis, is found, chiefly on the banks of creeks, as is a tea-tree with a black, slightly rough, but not papery bark. In the jarrah country of the south-west the saplings of most species will yield water, chiefly those of the jarrah, karri, and wandoo.

This area extends from New Norcia to Albany and eastward for 240 kilometres from Cape Leeuwin. It will not work, however, with saplings of the tall and beautiful salmon gums growing in the goldfields areas.

In South Australia water can be obtained from the trunks of saplings in the red-gum, manna-gum, stringybark, and a few other species. In Victoria it runs from saplings of many species of trees, and this holds good in the forests which stretch from Gippsland through New South Wales and Queensland to the tip of Cape York.

Other Forests

Along extensive stretches of our northern coastline there are belts of mangroves. No species of mangrove will yield water from either trunks or roots and one, the milky man-grove, when cut exudes a thick white juice which is a virulent poison. But scattered through the tangles of mangroves are patches of ground which are a little above the level of the highest tides and on these grows a tea-tree with a slender trunk and leaves bearing a superficial resemblance to those of a gum tree.

If cut off a little above ground level and again below the head of foliage, then turned upside down, these saplings drip water. Repeated tests in many places have shown that they are always reliable and the average tree-trunk yields at least quarter of a litre of clear water.

During the last war the writer’s work as a Bushcraft Instructor covered all the country mentioned in this chapter and never in any of the forests, except on the goldfields of Western Australia, was there a failure to demonstrate how a drink could be obtained from a sapling. The same thing has since been done with parties of bushwalkers in other areas of country where there was no surface water.

Unfortunately, there are a number of misconceptions about obtaining water from trees. One such story is that the bottle-trees of the Kimberleys in Western Australia and parts of Queensland have hollow trunks filled with water, which can be tapped with the aid of an axe or a tomahawk. It is a fact that a few old specimens, at the end of the wet season, do have water in hollow interiors, but in nearly every case it is a black, stinking liquid full of the decomposing bodies of insects.

Good drinking water can be obtained from both species of bottle-tree, however. In the Kimberleys of Western Australia, select a young one – the proper name of it is baobab, Andansonia gregorii – about 23 centimetres in diameter and cut a strip of bark from the trunk about 10 centimetres wide and 60 centimetres long. (Do not be one of those vandals who kill the tree by removing bark right round the trunk.)

Under the bark is a layer of soft, spongy sapwood. With the blade of a knife dig out small chunks and chew them. Each piece will yield about a teaspoon of water with a pleasant, sweetish taste and the wood is reduced to a wad of fibres.

In the case of the Queensland bottle tree, Brachychiton rupestris, a young one is selected and a V-shaped gash is cut through the bark and into the sapwood, with a piece of leaf or bark at the bottom to act as a spout. Drops of water run down the sides of the gash and can be caught in a container.

In each case, the appearance of the young tree is so distinctive that anyone can identify them at a glance. The shape of the trunk is exactly like that of a long-necked bottle.

In jungle (rain forest) drinking water is obtained from vines (lianas) or canes (rattans). The vine is cut through close to the root and again as high as one can reach. It is then cut into short pieces and each is turned upside down to let the water drain out. The first teaspoon or so should be allowed to run to waste, in order to wash away the stinging crystals (oxalate of lime) in the bark. It is a good plan to give each length of vine a point like a lead pencil instead of the slanting cut used in the case of water roots.

Never blow down or suck jungle vines, for those stinging crystals can cause a very sore mouth and throat. As was the case with roots, one must never drink anything from vines if it has a bitter, burning taste or a milky juice exudes from the bark.

A few experiments in an area of jungle will soon show which are the water vines there; they vary greatly in appearance, colour of wood when cut, and so on, depending on the locality. In New Britain the best water vine has no joints (nodes) and when cut the wood exhibits concentric rings of pink, cream, and white. In Dutch New Guinea and on Cape York Peninsula the best one has a rough, cork-like bark which rubs off in the hand. Farther south in Queensland the best water-yielder has well marked nodes at regular intervals and when cut it is a clear, cream-white colour with a small brown spot in the heart.

In the case of the rattan cane, easily identified by the midribs of the leaves being extended to form long, whip-like tentacles armed with rows of hooked saw-teeth, cut the cane into short lengths, blow down each, and the water will squirt from the other end.

Good drinking water is also contained in the giant Chinese bamboo. Select a stem which is about half grown, fell it, and locate the sections which contain the water by shaking it.

These are never at the bottom of the stem but usually about a third of the way up.

Two plants whose fleshy leaves will yield water in an emergency are the ‘pig-face’ (Carpobrotus) of the coastal sand dunes and the parakeelya (Calandrinia polyandra) which grows on inland sandhills after a good rain. The leaves are crushed between the hands and the juice is collected in a container. It has a sickly, metallic taste but causes no ill effects.

Along the northern coasts of Australia and on some islands a growth of tamarind, mango, and similar exotic trees on the shore of a sheltered bay marks a spot where Malays used to camp when making trading voyages to collect tortoiseshell and trepang. A water supply will always be found close by.

Misinformation

The reader is assured that all this data has been tested out, especially during the last war, when bushcraft instructors had to demonstrate it repeatedly to their classes. No competent man ever staged a flop by failing in a field demonstration.

There were plenty of failures, however, on the part of men who had listened to a few lectures, watched a few demonstrations, and then persuaded the C.O. of their unit that they were qualified to teach others. There are always people ready to bolt with an idea; in this particular instance, however, nearly all of them proceeded to show that a little learning is indeed a dangerous thing. The bushcraft student should avoid this trap by trying never to instruct others until he has mastered the subject thoroughly.

Another pitfall lies in accepting hearsay evidence as fact. It is natural to want to learn all one can by listening to those who may have something new to impart. Quite a lot of useful information can be picked up in that way, but one also hears a great deal of absolute nonsense. There is only one safe rule: no matter how good an informant’s statements may seem, do not believe a word of it until he has demonstrated it to you and you have also mastered it yourself. Some people will pass on secondhand information with all the assurance of a racing tipster giving out the names of winners, and, like the racecourse tout, they are more often wrong than right.

A typical example of misinformation is the statement, which has often appeared in print, that in northern Australia fresh water can be obtained at shallow depths by digging where the screw-pine (Pandanus) grows. This is so ridiculous that one can only marvel that people would pass on such an obvious fallacy. The screw-pine grows chiefly around coastal saltwater swamps or on soil so arid in the dry season that, as one experienced bushman put it, ‘You might dig right through to China without striking fresh water’.

There are at least three well-authenticated instances where that particular piece of misinformation nearly cost men their lives. In 1942 a similar piece of misinformation did cause a man to die of thirst. A soldier in the Armoured Division was told that in Western Australia the presence of the golden-flowered Christmas tree, Nuytsia floribunda, indicated fresh water at shallow depth.

He was on a truck which broke down near Three Springs and he took a shovel and wandered off into the scrub. He dug hole after hole under Christmas trees without finding as much as damp soil. Never having been shown how to get water from tree roots he went staggering past those which would have supplied him with a drink and ended by lying down to die under a ‘bull banshee’ (Banksia grandis) which is one of the best water-root trees in that part of the country.

There is a double lesson in the fate of that young man. It shows the criminal folly of passing on false information, and the need to try out all these things before an emergency arises.

Plant Identification

With regard to the identification of trees and plants, the beginner should not try to copy the expert who walks along and identifies—say—a messmate or grey box tree at a glance and often from quite a distance. The ability to do this can be acquired only by considerable practice.

When shown some new species, the beginner should examine it closely.

- Is the bark smooth or rough, loose or firm?

- What colour is it on the outside and on the inside when cut?

- Thick or thin? Cut through the sapwood into the heartwood, noting the colour and texture of each,

- Then look at the leaves, noting the colour and shape, whether they are of the same colour on both sides, and how the veins run.

- Finally, note every feature of the flowers, if the tree or plant is in bloom, and the buds and the fruits.

Put all the particulars in a notebook. It is not necessary to be able to recognise and to name all the flora of a region, of course; the bushman needs to know only those which are of some practical use. It is important, however, to be able to recognise all the forest trees. Forestry authorities in some states publish handbooks which provide information about the forest trees there.

The best practical guides to timber identification for the beginner are commercial beekeepers, whose living comes from the trees. They may know only the local popular names, but their identifications are always reliable. They can also distinguish species at a distance which seems incredible to the uninitiated. There is nothing mysterious about it; they do it by the colour of the foliage, the growth habits, the general shape, and the type of country on which it is growing.

A valuable aid to the beginner when learning tree identification is to wear amber-tinted glasses. Polaroid glass will not serve. By acting as a colour filter, the amber glass accentuates the various shades of green. Through them, some eucalypt foliage takes on a definite bluish tint and other species a brownish green. In time, anyone with a flair for the work should be able to identify at distances of over a kilometre on open country all the main species of eucalypts.

It is not advisable for the beginner to try to memorise the scientific names of trees, shrubs, and plants at the outset.

There is so much else to learn which is more important, but later it can and should be done, for without this additional knowledge many text-books on botany are almost useless.

Guides To Water

There are several guides to water in the form of lagoons, creek pools, rock-holes, springs, and soaks. King among them is the wild pigeon. Being a seed-eater, it must drink at least once a day in warm weather; in very hot weather it comes to drink at dawn as well as the usual time of around sunset. The flight of any species of wild pigeon is quite distinctive; a trained eye can identify these birds on the wing at any distance up to 400 metres. The best way to learn how to use them as a guide is to start at the end and work backwards.

Go to a bush waterhole about an hour before sunset, wearing neutral-tinted clothing or, better still, a khaki shirt and trousers mottled with a camouflage pattern of patches which have been dyed green. Stick some green twigs into the hatband and have others hanging in front of the face as an additional disguise. Sit down beside a tree, rock, or bush close to the bank and keep quite still. If the flies are troublesome, wear a green fly-net.

Pigeons will be seen to arrive, perch on trees for a time, flutter to the ground, walk to the water in a nervous, hesitant way, plunge in their heads, drink swiftly, and fly off. On the following evening, sit down about 200 metres away and watch for pigeons flying past, taking particular note of their characteristic flight and the way in which they head for the water-hole. On the third evening choose a spot a kilometre away and note how the lines of flight all converge on that waterhole.

Continue until you are quite sure that you can distinguish a pigeon from all other birds by its flight alone, then go into another area and locate a waterhole solely by using wild pigeons as guides. The day may come when this knowledge is very useful. Countless men in Australia have been saved from great hardships or death by these birds.

Here is one such case. In 1885 the South Australian Government sent my uncle, David Lindsay, from Adelaide to the Northern Territory to survey the Barkly Tableland, which had just been taken up on pastoral leases. My father, George Lindsay, then a lad of eighteen, accompanied the party. Under the date of 23 February 1886 his diary contains this entry:

Todd River, Madonnell Ranges. Everything parched with drought. Only a few pints left in the kegs. Camels and men prostrated. If we don’t get water we’ll perish.

My uncle took the strongest camel and rode off to look for water, but failed to find it. Ominously, there were no recent signs of Aborigines. Returning to camp that evening he saw a solitary rock pigeon flutter across the gorge ahead of him. He noted the line of light, followed it up a hill, and, in a spot where nobody would expect to find water, came to a rockhole containing thousands of litres.

Several days later the party met the first Aborigines they had seen in the ranges. They stated that the drought had driven them away from the Todd country; it was a case of

‘kwadja kwiandaridjika’ (water all gone) there. There was only one place where water could still be found; a rockhole high on a rugged hillside. It was the one to which the pigeon had guided my uncle, so if it had not been for that one bird-and my uncle’s knowledge of what it indicated-the entire party might have perished.

No bushman worthy of the name will shoot a wild pigeon unless no other food is obtainable. These beautiful, harmless birds have saved many a human life and might save his own some day.

A full list of the wild pigeons and doves of Australia will be found in any good bird book; Neville Cayley’s What Bird is That? is specially recommended on account of its colour plates. Those species most useful to the bushman are the bronze-wing (Phaps chalcoptera), as large as the domestic pigeon; the crested pigeon (Ocyphaps lophotes) of the dry inland regions, and the white-quilled rock pigeon (Petrophassa albipennis) of the Kimberleys, specially useful there in the dry season because it lives in the sandstone areas where water would otherwise be so hard to find.

The student who lives in Adelaide, Melbourne, or Sydney can visit the Zoological Gardens, see specimens of our wild pigeons and doves in captivity, and thus learn to identify them before going bush. Or get to know birds by carrying a small pair of binoculars and a bird ID app. Ed.

Many of our finches are never found far from water in hot weather. Probably the best as a guide is the zebra finch (Poephila guttata), also known as the chestnut-eared finch and the headache bird. Its monotonous chirp of ‘Teut-teut, teut-teut’ is unmistakable. In fact, all seed-eating birds indicate by their presence that there is water in an area, although some, such as the black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus species) may fly a long way to feed every day.

The best training for a student, as was mentioned in the case of the wild pigeons, is to go to a waterhole in arid country and watch for all the species which come to drink there from late in the afternoon until dusk. Later, their flights towards that waterhole should be observed from vantage points on the surrounding country. It would be difficult to over-stress the importance of this and every other form of ‘learning by doing’ as part of the training.

Animal pads are not infallible guides to water but they can be very useful. When following one, remember that if other pads converge on it the right direction has been taken, but beware of following one in the direction where it forks repeatedly and grows fainter, for then one is heading in the wrong direction. It is also worth remembering that cattle usually drop their dung after drinking and not on the way in to water.

In many parts of Australia, domestic bees have now gone wild and make their hives in hollow trees. They cannot live without water and so can be used as a guide, but there is a knack in it. Most of the workers who fly from the entrance are honey or pollen gatherers, but as these scatter to all points of the compass they can be disregarded. The ones to watch for are those which form a regular air-lane towards one particular point as they go out to get water and return laden with it.

If you move around so that the sun is at the right angle, this watering flight shows up as a line of glittering specks. The waterhole is seldom more than 400 metres away.

Finding Underground Water

There are places where water can be obtained at shallow depth by digging. One is in the sandy beds of those inland creeks which run only after a heavy rain. In searching for a spot where a soak might be found, there are three signs:

- Tracks of dingoes or horses, with deep hollows made by scratching or pawing.

- Numerous little burrows under the bank on the shaded side, each with a pile of pellets of mud before it. These are the burrows of freshwater crayfish (yabbies) which go down to water or wet sand.

- Timber on the bank with a very fresh, green, and vigorous head of foliage. These are usually upstream from the place where a bar of rock runs across the bed.

By digging at any of these spots there is a good chance of striking a supply of water, but sometimes there is only damp sand overlaying a bed of clay. If a hollow is made in this clay, however, a little water may collect during the night.

Another fairly reliable guide is a patch of water rushes, Juncus pallidus, at least 2 metres tall and flourishing in appearance, in a gully or at the foot of a hill. These rushes are easily recognised by their smooth green stems and a bunch of brown flowers near the tip. It is useless to dig where they are stunted, thin-stemmed, and only a metre or so in height.

In country where big, dome-shaped masses of granite outcrop in the plains, there is sometimes a flourishing group of trees or bushes beside one. Those rocks shed water like an iron roof when it rains and most of it is lost in the soil, but occasionally there is a hollow in the rock under the ground, filled with sand or gravel. This may hold water for some time and its presence would never be suspected but for the vegetation above it. Water can sometimes be struck by digging among the trees or bushes, although it is usually a long way down.

Redgums in eastern and southern Australia, and flooded gums in Western Australia, when growing on the banks of water-courses, indicate that any water found by digging there will be fresh enough to drink.

Where an inland creek debouches on a plain through a gap in a range, the floods carry down sand, gravel, and mud which build up a fan-shaped ‘cone of dejectment’ on the plain. This area is usually marked by a grove of sizeable red-gum trees whose flourishing appearance shows that their roots are drawing water from the sand and gravel below. The best place for a well is among the big trees close to where the creek emerges from the hills.

Fresh Water In Sand

The statement that ‘Fresh water can be obtained by digging on sea beaches above the high-tide mark’ has often appeared in print and has been quoted widely. The writer was one of the Army instructors who, during the last war, dug holes on beaches along two-thirds of the coastline of Australia. It wasn’t done to demonstrate a method of obtaining a drink in an emergency, but to show how slender are the chances of striking water there which is fresh enough to drink.

(In passing: a fitting punishment for the type of person who helps to perpetuate this fallacy would be to give him a meal of salt fish, with nothing to drink, then hand him a shovel, point to the beach, and invite him to put his theories to the test—or go thirsty.)

Fresh water can be obtained on some of our beaches but such spots are often few and far apart. Where sandstone outcrops along the shore, threads of more or less fresh water can sometimes be found trickling down the sand at low tide.

Seeps of fresh water are fairly common where limestone cliffs overlay a granite bedrock. Both can often be located by watching flocks of land birds arriving to drink there.

A surprising number of fresh-water springs around our coasts are uncovered only at low tide. They can be located by animal tracks across the beach and, on a hot day, flocks of finches and other seed-eating birds perched on shoreline trees and bushes, waiting for the tide to ebb.

Where large sand dunes lie behind a beach it is usually possible to get fresh water by digging. Look for a big hillock of bare drift-sand, standing at least 100 metres from the high-tide mark. Find the deepest hollow around its base and dig close to the slope of the dune. If the hole is more than about a metre deep—it is sometimes necessary to sink to a depth of 3 or 4 metres —the sides must be timbered with stout sticks or planks of driftwood.

This is most important. Sand caves in without any warning and has caused many deaths, particularly among children who have excavated holes to serve as play-houses in the sides of sandhills. If no timber is available, give the sides a good slope.

A round hole is less likely to cave in than a square one.

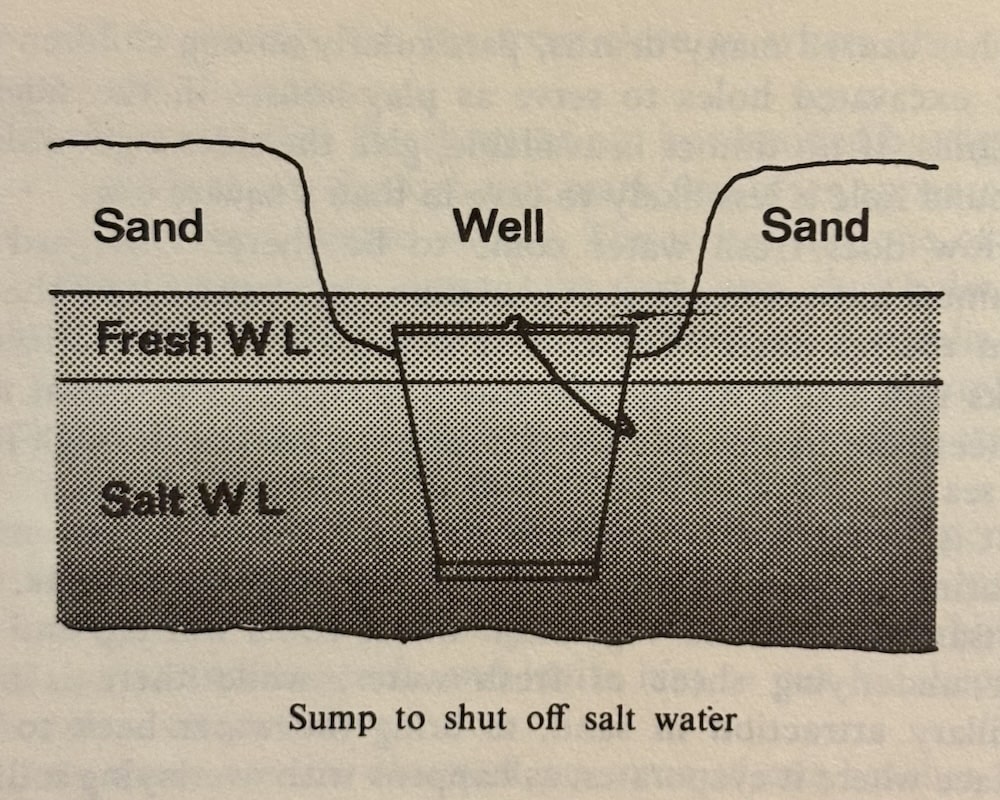

How does fresh water come to be there? Disregard the common but nonsensical explanation that ‘sand filters the salt from the sea-water’. The correct explanation is that driftsand soaks rain like a sponge and this water percolates down until it meets the bed of salt water which has soaked through from the sea.

It is a curious fact that fresh water will float for ever on top of brine without mixing, like cream on a pan of milk. On driftsand there is no vegetation whose roots will tap and use that underlying sheet of fresh water, while there is little capillary attraction in sand, to bring the water back to the surface where it evaporates, as happens with overlaying soil.

Every big hill of driftsand is therefore a potential catcher and storer of rainwater and the well at its base is designed to tap that saucer-shaped ‘cream’ of fresh water beneath it. The well must be a fair distance from the beach to escape the rise-and-fall influence of the tides.

Quite often, when one of these sand-wells is used, the water in it becomes salt and stays salt. This is because the underlying brine has been drawn up by bailing out supplies. This can be overcome by using a bucket, a drum with the top removed, or even a wooden box whose joints have been caulked to turn it into an impervious sump. Sink it in the bottom of the hole until its upper edge is about 25 millimetres below the surface of the water.

Now bail gently for some time, taking care that the water removed from the sump is thrown as far from the well as possible. Stop when the water inside the sump is fresh. The bucket, drum, or watertight box shuts off the salt water and the only water which can now enter it flows from the top (fresh) layer.

Fresh water can sometimes be found in this same way by digging in the dunes which fringe many of our inland salt lakes.

Some tribes of Australian Aborigines, and the Bushmen of the Kalahari in South Africa, did not have to dig holes to secure the water which lies under stretches of sand in beds of creeks. Around some permanent waters a bamboo-like reed grows. A length of this was cut and the joints were knocked out by ramming with a long, thin, and stiff stick. A number of these reeds were carried when the family groups moved out into country where there was no surface water but plenty of game animals, which obtained sufficient moisture for their needs from succulent plants such as the parakeelya.

The haft of a spear was driven into a bed of sand in a creek where the vegetation showed that water lay below. The spear was rotated and moved up and down all the time to prevent it from sticking in the hole. The task requires both skill and patience, but when the water was reached, indicated by a squelching sound, the spear was withdrawn swiftly and the reed, with a bunch of dry grass tied around the lower end, was put in its place as quickly as possible.

This grass held back the sand and, by sucking the top of the reed at intervals, a mouthful of water was drawn up every half-minute or so. A modern adaptation of this ancient device, the spear-pump, consists of a length of steel piping. The lower end is pointed and is provided with a number of very narrow vertical slots, which hold back the sand but allow water to enter. It is driven into a sand bed until the water is reached, then a small pump is screwed to the upper end. Many of these spear-pumps were used by the Light Horse in Sinai during the first World War.

Another valuable guide to water is the presence in coastal sand dunes of large mounds of the shells of cockles and other edible shellfish, mixed with ashes, pieces of calcined bones, and fire-splintered stones, with a scattering of chips of flint, quartz, chert, or other very hard rocks on the surrounding ground. These mark a spot where Aborigines used to camp and indicate that there should be a good spot for a sand-well close by.

Common sense must be used when following up this particular clue. The effects of erosion must be taken into account, as well as the fact that some such supplies are seasonal, existing only after a heavy rain. Further, Aborigines never camped right alongside a water supply. They camped a few hundred metres from it, allowing the game to come there to drink.

As they put it, ‘only the silly white feller’ camps on the bank of a waterhole or spring or right alongside a soakage well, thus preventing birds and animals from drinking there and forcing them to move to another supply.

Collecting Dew and Rain

Dew is a valuable standby. With the aid of a small piece of sponge, a piece of cloth, or even a wad of chewed dry grass it can be sopped from leaves or stones at sunrise. It can be shaken from the foliage of fine-leafed plants and caught in a piece of plastic or other waterproof material, or in a billycan or tin dish. It can also be shaken from flowers such as those of the banksia or bottlebrush. The desert Aborigines often relied on dew for part of the year and tests have shown that we can also collect enough for a day’s supply in the same way.

In desert country, however, one must work hard and fast, for dew cannot be collected until it is light enough to see and the dew dries up with surprising swiftness as soon as the sun rises or the dawn wind starts to blow.

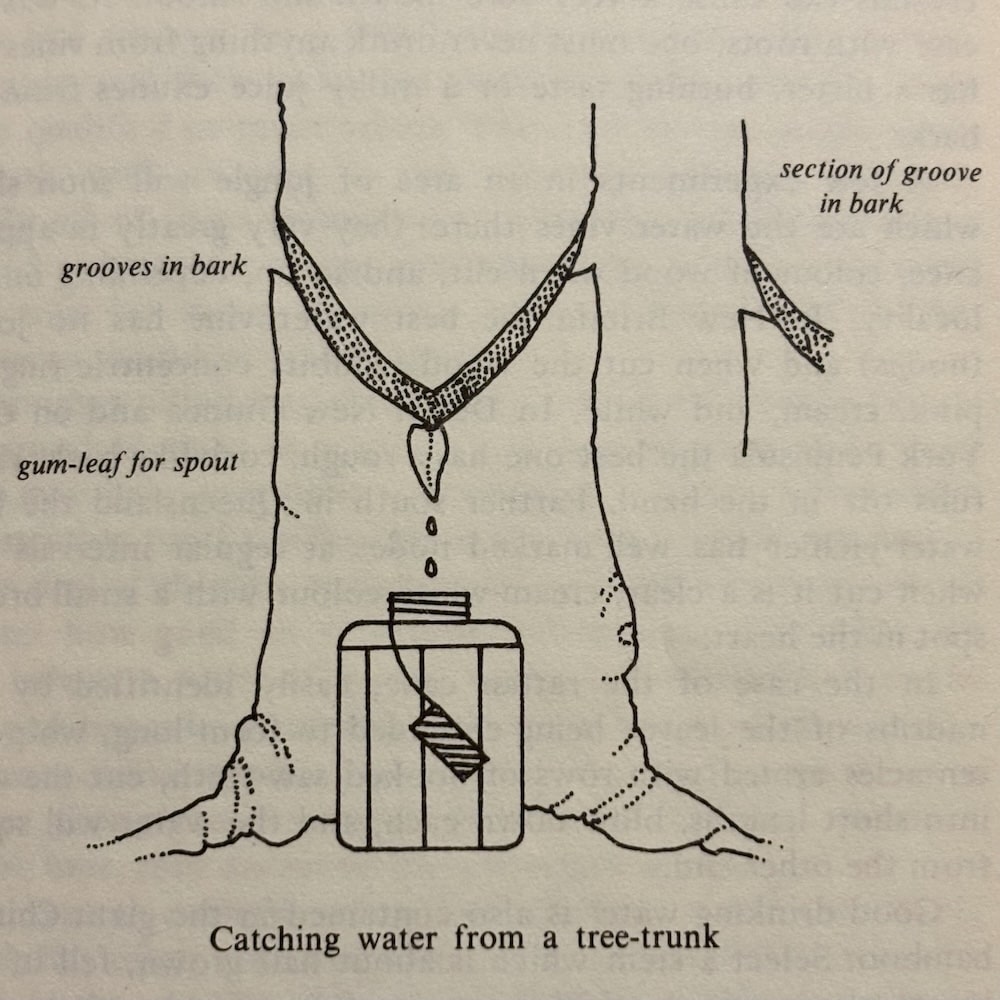

To catch rainwater in the absence of a waterproof sheet, select a smooth-barked tree or a palm and cut two slanting grooves around the trunk, about 25 millimetres deep and meeting in a V. Give the lower edge of the groove an inward slope so it will act as a gutter and attach a piece of leaf at the bottom of the V to serve as a spout. Tests have shown that during a short, heavy shower, up to 9 litres can be caught in this way from the trunk of a single tree.

On some Pacific atolls, where there is no surface fresh water and it can seldom be obtained by digging a well, natives use the trunks of coconut palms in the same way, although they prefer to tie a strip of pandanus leaf around the trunk instead of cutting a groove. Shells of the giant clam (Tridacna) which hold several litres are used to catch the water.

Water Divining

No advice on water finding would be complete without mentioning the divining rod, in which some people have an unshakable faith, in spite of the fact that it has been given numerous scientific tests and has fallen down every time. One such test was carried out by the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission of New South Wales. Between 1918 and 1943, 2758 bores were sunk in central New South Wales to provide water supplies for settlers. Of these, 1284 sites were chosen by people who claimed to be able to use the divining rod and of these 70.5 per cent struck good supplies. But 1474 bores were sunk without the aid of a diviner to select the site and of these 83.8 per cent struck good supplies!

Even more striking are the figures for bores which did not strike water of any kind. On the divined sites there were 268 of these failures, but on those not selected by a diviner there were only 131 failures.

Similar results have followed with tests elsewhere in Australia and in other parts of the world. One of the most amusing was carried out by Professor Sir Kerr Grant a few kilometres from Adelaide, South Australia. He conducted some divining rod ‘experts’ one at a time and out of sight of the others across a paddock. Most of them selected sites which differed from those chosen by the rest— and not one picked the spot where the big trunk water main from the Happy Valley reservoir runs under that land!

Fresh Water From Salt

With the aid of a simple distilling apparatus, all the drinking water required by a small party can be obtained from sea water or the brine or brackish water in a salt lake.

In an emergency, any billycan or saucepan with a lid can be used as a still, although the bigger it is the better. It is half-filled with salt water, the lid is put on, and it is stood on a fire in the shade. In this case the water must not boil; it is merely heated until drops condense on the underside of the lid. Every few minutes the lid is lifted off with great care —the least jar will dislodge the drops of water-and is given a shake over a plate or a piece of waterproof sheeting.

The police records of Western Australia list seven cases where men have died of thirst through not knowing this simple trick. Each had a billycan with him, as well as matches, and had reached a lake of salt water.

Another method is to boil the salt water in the billycan without a lid and to hold in the steam, with the aid of a couple of sticks, a towel, or any similar piece of cloth. As soon as it becomes sodden with condensed steam, the cloth is wrung out.

It takes several hours to obtain a litre of condensed water by this method, but that is sufficient to keep a human being alive in the hottest weather.

It is even possible to distil water from the earth. Dig it up from the shady side of a boulder, especially from where it has been covered by flat stones. Disregard the fact that it seems to be quite dry. Place it in a seamless container with a lid – the ordinary tin billycan cannot be used because the solder in the seams will melt – stand it on hot coals and every few minutes remove the lid and shake off the drops of water which have condensed on its under side.

When no more moisture collects under the lid, tip out the earth and replace it with a fresh lot. It is best done at first light of dawn, for then soil moisture has been brought to the surface by capillary attraction during the night.

Next Article: Carrying Out Toilet Waste

Interesting article (not that i have read it all) – I’ll try and remember to try for some water mallee roots when next in outback SA!